Coal’s Frontmen in Oakland: Who owns TLS?

Terminal Logistics Solutions (TLS), the newly created terminal operator hoping to ship millions of tons of coal annually through a new export facility in Oakland, may, in fact, be a subsidiary of Bowie Resource Partners LLC, the coal company whose Utah mines the terminal would serve, according to documents provided by Emery County, Utah, in response to a Sierra Club public records act request.

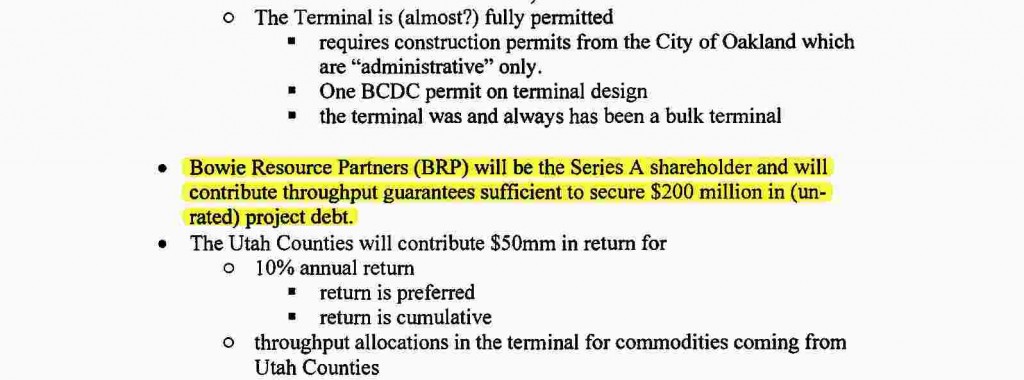

An email from investment banker Jeffrey Holt to public officials in Utah in March 2015 reveals a bold plan to create TLS as part of “the business arrangement” between Bowie, four Utah counties, and possible other users of the terminal. A term sheet accompanying Holt’s email reveals details of a plan to create TLS to operate the Oakland Bulk and Oversized Terminal (OBOT) and finance the whole undertaking with a combination of government largesse and loans from pension funds. Under the plan, Bowie would be “the Series A shareholder” in the new company, a venture capital arrangement that could give Bowie a controlling interest in TLS. (See UPDATE at end of article: Bowie admits to a “vested interest” in TLS.)

Excerpt from term sheet sent by Jeffrey Holt to public officials, March 25, 2015. Source: Emery County, Utah

The term sheet also suggests that once the terminal is up and running, the amount of coal shipped through it might not be limited to 49% of the terminal’s full capacity as has been suggested in some presentations by coal proponents. The document states that the terminal “will handle 9.5 [million] metric tons of bulk product per year, both white products (soda ash, potash, salt) as well as black product (coal)” with coal “not to initially exceed 49% of throughput on an annual basis.” However, the initial 49% limit is described as an “internal policy only, not restricted by permits.” By implication, the terminal’s entire estimated 9.5 million-ton throughput could be allocated to coal once the terminal gets past the political and legal hurdles that currently block its path.

TLS’s Public Image

If the documents accurately reflect TLS’s origins and ownership, the reality would be in stark contrast to the public image TLS has cultivated. At Oakland City Council meetings, TLS has left the impression that it is an Oakland-based startup that will bring numerous jobs to the Oakland waterfront and boost the local economy. Jerry Bridges and Omar Benjamin, the president and senior vice president of TLS, respectively, are well known former executive directors of the Port of Oakland. To promote TLS’s image as a local job creator, Jerry Bridges has shown up at Oakland City Council Meetings flanked by members of the Ecumenical Economic Empowerment Council, a group of 14 Black pastors who have praised TLS for its potential to reduce the unemployment of young Black men in Oakland.

Jerry Bridges, President and CEO of Terminal Logistics Solutions Credit: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Critics of the coal plan have pointed out that the same number of jobs, if not more, will be created if other commodities are featured and that very few of the permanent jobs at the former Oakland Army Base will be at the bulk terminal. City officials, for their part, have taken a strong stand against coal. In June 2014, the City Council enacted a unanimous resolution in opposing the transportation of hazardous fossil fuels, including coal, through the City of Oakland.

As the campaign against coal exports has won over public opinion, including editorial support from the Oakland Tribune, City officials and anti-coal activists have repeatedly wondered out loud why TLS doesn’t give up on coal and look for other, less controversial, commodities to ship through Oakland’s new bulk commodities terminal.

The answer may be that TLS is not the home-grown startup of its image, but simply a subsidiary of a coal company that wants to ship coal through Oakland for the next 66 years. Other commodities may play a role in TLS’s plans, but coal appears to be in its DNA.

If bringing coal to Oakland sounds audacious, Bowie is nothing if not audacious. Fueled by private capital willing to gamble on future overseas demand for the world’s dirtiest and most carbon-intensive fossil fuel, Bowie has aggressively expanded at the very time that domestic demand for coal has collapsed. As long-time leaders in the coal mining industry fall into financial disarray, Bowie has been picking up their coal mines in Utah and other Western states at bargain basement prices or with heavily leveraged buyouts. Although Bowie’s high-risk, high-stakes strategy has encountered recent storm clouds, the company’s growth has been spectacularly rapid.

In 2013, Bowie bought the largest coal mines in Utah and looked to Oakland, which had already approved the creation of a new bulk commodity terminal, as an ideal gateway to Asian markets for Utah coal. Phil Tagami, the master developer of the former Oakland Army Base, had assured Oakland in December 2013 that rumors of a plan to ship coal were unfounded but, it appears that, at some point in 2014, he began to work with Jeffrey Holt, an investment banker in Utah, on a 66-year deal to ship coal from four Utah counties through the new terminal to be built near the Bay Bridge toll plaza.

“The script was to downplay coal.”

Bowie’s targeting of Oakland was supposed to be kept under the radar. “The script,” dealmaker Jeffrey Holt wrote in an email to Utah government officials and others, “was to downplay coal.” But in April 2015, the plan to turn the former Oakland Army Base into the largest coal export facility on the West Coast burst into public view when the Utah Community Impact Board approved a $53 million loan of public funds to four Utah counties for investment in the OBOT. The Community Impact Board disburses rebates of royalties from mining on federal lands to county and local governments for projects to mitigate the impacts of the mining activities within their borders.

Enough details emerged of the deal to evoke an immediate uproar in Oakland. Environmental groups quickly built an alliance with labor, faith, economic justice, and other community groups to demand that the City Council consider a ban on coal, and, in September 2015, the Council held a public hearing on health and safety impacts of coal exports, a step required before the City Council could pass an ordinance banning coal exports.

The financial details of the coal export plan remained somewhat opaque. In September 2015, Tom Sanzillo of the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis prepared a comprehensive analysis of the economics of the coal exports project that was submitted by Earthjustice at last September’s public hearing. Sanzillo’s analysis explored everything that was publicly known about the financial aspects of the proposal to ship coal through Oakland, as well the economics of the coal industry, and concluded that, “[f]rom Day One, the coal component of the [Oakland Army Base] project will be a financial drain on the City of Oakland, and will remain so for the foreseeable future.”

Sanzillo analyzed published reports and emails that revealed many aspects of the transaction, but noted that, the published minutes and public records disclosed by the State of Utah did not “provide details of the actual legal structure of the transaction, including how the funds would be transferred from the State of Utah or its counties to the Oakland Army Base, City of Oakland, Port of Oakland, the developer (CCIG) or any other party.”

Email to County Officials Reveals Plan

The new documents–an email dated March 25, 2015, from Jeffrey Holt to numerous public officials in Utah, and three attachments–begin to fill in the gaps. They reveal publicly for the first time that TLS, the proposed operator of OBOT and an entity with no track record of ever having run anything, was conceived by Holt as an alter ego of Bowie—a local front for the coal company rather than a truly independent Oakland-based entity.

The plan is outlined in one of the attachments to Holt’s email, a “Preliminary Term Sheet” for the multi-commodity bulk export terminal to be built in Oakland. The term sheet states, “TLS will be created as part of the business arrangement between the [four Utah] Counties, Bowie, and any other users [of OBOT] that can be contracted ahead of time, and will own a 66-year operating concession on the terminal from the City of Oakland.”

According to the term sheet, the plan included the following points:

- The Oakland terminal would cost a total of $275 million dollars.

- Bowie would “contribute throughput guarantees sufficient to secure $200 million in (unrated) project debt” from pension funds, in exchange for which Bowie would be “the Series A shareholder,” a status implying that Bowie would hold all voting stock in TLS.

- The four counties will pay in $50 million and receive preferred (i.e., nonvoting) shares that would pay quarterly returns out of TLS profits.

- The remaining $25 million would come “from local California sources (for site prep and some waterfront infrastructure).” There is no mention of any equity in exchange for this contribution and it is not clear whether this refers to private or government money.

The term sheet also describes the terminal as “(almost?) fully permitted,” explaining that it “requires permits from the City of Oakland which are ‘administrative’ only,” an apparent reference to building permits. According to recent statements by Assistant City Administrator Claudia Cappio, no applications for building permits have been submitted.

The author of the Preliminary Term Sheet appears to be Holt himself. In a second email attachment, a March 25, 2015 memorandum that accompanies the term sheet, Holt identifies himself as the “Strategic Infrastructure Advisor” to the four coal counties that were to obtain the money for their investment in TLS through a loan administered by Utah’s Community Impact Board.

Holt’s role was by no means limited to providing “advice” to the four counties. Holt is an investment banker and managing director of BMO Capital Markets Inc., the investment banking arm of Canada’s Bank of Montreal, and had been serving as chairman of Utah’s Transportation Commission since 2009. His bank could earn fees advising the counties, more fees putting together the deal for Bowie, more fees from a related rail project, and yet more fees from providing pension funds with the opportunity to lend their money to TLS.

In his memorandum, Holt stated that raising money from the CIB was “necessary now to show the debt investors in the terminal [i.e., pension funds] and the lessor of the land (CCIG [i.e., Phil Tagami’s company]) that the Counties are legitimate partners (with funds in hand) and committed to working through negotiations to a financial close.” To that end, Holt, who had, until recently, been a member of the CIB, would take the lead on the presentation to the CIB.

All of this planning was concealed from public view until April 2, 2015 when the Community Impact Board heard Holt’s presentation and promptly approved a $53 million loan to the four counties, subject to review by Utah’s attorney general. According to the term sheet, $3 million would be allocated to advisory fees, transaction costs, legal expenses, and outside technical experts, leaving the counties with a balance of $50 million to invest in TLS.

As news of public funding for a private coal terminal project in Oakland emerged, Holt emailed commissioners of the four Utah counties, writing: “We’ve had an unfortunate article appear on the terminal project. If anything needs to be said, the script was to downplay coal, and discuss bulk products and a bulk terminal.” Holt also wrote that Phil Tagami, the master developer of the former Oakland Army Base, was disappointed that the plan to export coal had become public. According to an August 2015 article in the East Bay Express, public records show that the viability of Bowie’s plan to mine coal in Utah could depend on the Oakland export facility and that the company might not otherwise find a market for the fossil fuel.

In December 2015, Holt abruptly resigned from the Utah Transportation Commission and moved his family from Utah to New York but he is presumably still hoping to close the deal. Meanwhile, the identity of the pension funds he was planning to line up for the $200 million investment is unknown. Given Holt’s role working for BMO Capital, it appears likely that BMO Capital stood to get a cut of any deal that would fund TLS while providing the controlling interest in TLS to Bowie.

Pension Funds Targeted for Investment in Bowie’s Coal Project Could Be Left Holding the Bag

The deal outlined in the Preliminary Term Sheet and Holt’s accompanying memorandum does not suggest that BMO Capital planned to make any investment of its own capital in TLS, but rather that TLS would be largely funded by unrated debt foisted on pension funds. Pension funds and the four Utah counties would put up all the money, Bowie would get all the voting stock, BMO Capital would make its money from advisory fees, and, if the whole scheme collapsed because, say, overseas demand for coal did not meet expectations, the pensioners whose retirement savings were invested in the plan and the people of Oakland and Utah, who expected returns on the investment of their public funds, would be left holding the bag.

Ironically, the attempt to use pension money to fund the construction of new coal infrastructure comes at a time when many pension funds are trying to get out of investments in fossil fuels. California has recently adopted a law requiring its two major public pension plans, California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) and California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS), to divest from coal assets. Governor Brown signed the bill in October. Combined, the two pension funds represent more than 2.4 million retirees and are worth nearly $500 billion. Being the two biggest pension funds in the country, they are frequently viewed as trend-setters.

Still, pension fund trustees are vulnerable to a sales pitch that promises high returns yet omits important details of investments. Traditional investments such as stocks and bonds are projected to have relatively meagre returns in the coming decade, and pension funds are under pressure to find investments that will enable them to catch up with their future liabilities. In recent years, pension fund trustees have been approached by hedge fund managers and a variety of pitchmen for unrated debt and private equity opportunities. Although such investments are often marked by opacity and higher fees, some funds can be lured to invest a portion of their assets in private, unregulated investment fund in the quest for higher returns.

But fossil fuels are not the most attractive private investments. In an analysis published last November, a Canadian research firm found that 14 of the world’s largest public pension plans with collective assets in excess of $1 trillion US had lost $22 billion by not divesting their coal, oil and gas stocks in 2012. Conservative bankers are now taking seriously the prospect that new coal infrastructure may wind up as “stranded assets.”

Despite the recent bad track record of fossil fuel investments and the potential for a worldwide collapse of coal markets, BMO Capital apparently hopes to find pension funds willing to lend hundreds of millions of dollars for coal infrastructure in Oakland without requiring any evaluation of the debt by a reputable rating agency. “In the energy space, we believe there is a wall of cash from private equity and pension funds looking to find a home, which we estimate, from a dry-powder perspective, to be US$175 billion when we take into account private equity and pension funds chasing energy opportunities,” says John Armstrong, one of Holt’s colleagues at BMO Capital.

BMO Capital Markets “teaser” showing how Jeff Holt would market the opportunity to invest in the Oakland bulk commodities terminal

Demonstrating how BMO would promote investment in the Oakland coal terminal, another attachment to Jeffrey Holt’s March 25, 2015 email is a “teaser”—a colorful one-page summary of the private debt offering from TLS sponsored by BMO Capital Markets. The teaser describes the OBOT project as a “Deep Draft West Coast Multi-Commodity Bulk Terminal” located on the “West Coast, U.S.” Without irony, the teaser observes that the project “has received broad Governmental support,” failing to mention the 2014 resolution of the Oakland City Council opposing any shipments of fossil fuels through Oakland. Perhaps the support to which BMO referred was the hundreds of millions of dollars of public money that has been spent on infrastructure (so-called “horizontal construction”) preparing the former army base for its new private profit-oriented tenants.

BMO’s teaser optimistically projects the beginning of construction in August 2015. The term sheet states that the goal was “to allow the Terminal Project to be accomplished (financial close) prior to the expiration of TLS’s option on the terminal site in July.” This calls into question the legal basis for Phil Tagami’s threats to sue the City of Oakland. As of September 2015, when the City Council held its public hearing on the health and safety impacts of the TLS plan, the private commitments to close the deal had already missed the deadline.

Tagami reportedly extended the deadline to October 17, and there is no indication that TLS was able to exercise its option by that date. Indeed, the Los Angeles Times reports today that a lawyer for developer Phil Tagami said in an email that Terminal Logistics Solutions had not yet exercised its option to develop the terminal.

If there are pension funds out there waiting to invest $200 million in Bowie’s coal terminal, their identity has yet to surface. It is hard to imagine that pension trustees, required by law to exercise due diligence in reviewing prospective investments, would not have discovered the problems with coal investments, and investment in this particular coal terminal, described in detail in the Sanzillo report. Unless, that is, the real destination of their investments was concealed.

The $50 million investment from the four coal counties has remained in limbo since it was not approved by the Utah attorney general, whose signoff the Community Impact Board required as a condition for final approval of the loan to fund the four counties’ investment in TLS.

Whether the Utah legislature’s newly enacted bill directing $53 million to support the coal terminal project from other accounts actually circumvents the legal problems with using public money to finance a private firm’s construction of a coal export facility in Oakland has yet to be determined, but attorneys for environmental groups have expressed doubt that the arrangement will survive legal challenge.

UPDATE: After this article was posted, the Salt Lake Tribune reported that Bowie’s executive chairman John Siegel acknowledged his firm “has a vested interest in” TLS. See Brian Maffly, Proponents buried coal’s role in Oakland export terminal; now questions remain (Salt Lake Tribune, March 27, 2016). The Tribune also reported that, besides the State of Utah, no other investors in the $275 million terminal are known. According to the Tribune, BMO Capital Markets “is seeking $200 million from private investors, and is marketing the opportunity to pension funds.” In an earlier story, the Tribune reported that Carbon County Commissioner Jae Potter, a key proponent of Utah’s investment in the Oakland coal export scheme, confirmed that BMO is “packaging the needed $200 million in private investment as unrated debt to be sold to pension funds.” See Brian Maffly, Utah’s coal-export deal still faces high hurdles (Salt Lake Tribune, March 18, 2016).